The demand for certainty is one which is natural to man, but is nevertheless an intellectual vice. So long as men are not trained to withhold judgment in the absence of evidence, they will be led astray by cocksure prophets, and it is likely that their leaders will be either ignorant fanatics or dishonest charlatans. To endure uncertainty is difficult, but so are most of the other virtues.

— Bertrand Russell 1

The doctrine that the truth is manifest is the root of all tyranny.

— Karl Popper 2

Introduction

When we face the fallibility of our minds, the only reasonable way to hold a belief is with uncertainty. Yet, we have a palpable need to latch onto certainty, even if it is completely false. The horror we experience when we face our ignorance drives us to the safety of what we want to believe rather than the truth. Our cultures also reinforce this desire through the idealization of certainty. We look up to someone who “stays true to their values” as a confident leader. Those who are uncertain are outcasts that are spiraling into mental turmoil with their constant overthinking. With social and cognitive pressures preventing us from changing our minds we will helplessly struggle against the truth. We all have the experience of trying to convince the most stubborn person we know of something that we think is obviously true. We cry out to the heavens, “I’m presenting them with all of these facts and all of this data, my arguments are well constructed. How can they still not budge?” Then the horrifying reality sets in: nothing we can show them or say to them will make them change their mind. Our minds can and will convince us of anything. The human brain is not designed to tell us the truth.3 With the cards stacked against us, how can we make any progress?

My goal in this article is to challenge common ideas we have around uncertainty and elaborate its utility in coping with our fallibility. To accomplish this I am making two claims that I will argue for:

- Uncertainty is useful.

- Being uncertain is a virtue.

Finally, I will explain why we latch onto certainty and what we can do about it.

Uncertainty Is Useful

Pop psychology and cultural myths can make it hard to accept that uncertainty could be useful. We often associate uncertainty with indecision and neuroticism which are not “useful” emotions. I don’t argue for a type of uncertainty that entails these emotions. Rather, I advocate for a lack of certainty for all knowledge and beliefs. This doesn’t mean that we can’t use knowledge or believe something, it just means that we are open to the possibility of being wrong, or a little bit wrong. This is a subtle but powerful shift in mindset that can make us more robust in the face of new information. Instead of dying on a hill for a false belief we can adapt to a more true belief.4 Or, accepting uncertainty in our knowledge can motivate us to seek out information that fills in gaps in our knowledge.

Let’s start with a simple example to illustrate this point. Say you are trying to build a fence but you objectively do not know how. Your mind can create two options for yourself: assert that you know how to build a fence or admit that you do not know how. The first option seems utterly ridiculous, why would your mind tell you that you know how to do something when you clearly do not? We’ll get into these reasons later, but right now this example is to illustrate the utter irrationality of certainty in this situation. The more clearly useful option is to admit that you do not know how to build a fence so you can seek out instructions or help. As we can see in this example, uncertainty is a cognitive tool that allows us to obtain useful knowledge and beliefs.

Another example, is the cultural shift that occurred at the time of the Scientific Revolution. As Yuval Noah Harari says in his book Sapiens,

The Scientific Revolution has not been a revolution of knowledge. It has been above all a revolution of ignorance.5

Harari explains how humans sought all of their knowledge in religion before the Scientific Revolution. People thought that religious texts contained everything humans needed to know and if a religious text didn’t contain some information then it was considered irrelevant for humans to know. The certainty that religion provided us stifled our progress. As soon as we admitted that we didn’t have all the answers there was an explosion of scientific and technological progress. The last 500 years since the scientific revolution has seen growth many orders of magnitude greater than the 3000 years before the scientific revolution. Uncertainty has led to all of our modern luxuries and innovations. We would never have medicine, sky scrapers, computers, or cars if someone did not say, “I don’t know.”

Claiming that uncertainty is useful rests upon a minor form of philosophical skepticism. Philosophical skepticism in its extreme claims that it is impossible to know anything. The form I am endorsing for this argument is that our relationship to the truth is asymptotic. We can get closer and closer but we will never reach it with certainty. All knowledge and beliefs are provisional and subject to be proven wrong, despite some beliefs being more or less true given the current evidence (it’s important to note that this does not imply epistemic relativism). This is one of the more popular epistemological positions among philosophers today known as fallibilism.6 In fact, it is no surprise that it is related to modern science’s commitment to falsifiability. Scientific theories do not prove anything, they can only be disproven.7 This is a necessary building block in my argument because if we ever reached a point where a single person, or humanity as a whole, absolutely knew everything about the world, then there would be no purpose in being uncertain. In this case, uncertainty would simply be an irrational worry. There is a rich history of literature on defense of philosophical skepticism, but fully expanding on it would deviate too far from the current argument. I’d like to give a more intuitive, less theoretical explanation for fallibilism that has been given many times before.

The first point that is often used in some form to argue for philosophical skepticism: the human mind is fallible. We have emotions, desires, perceptions, and biases that prevent us from seeing reality objectively. We can easily be fooled with illusions and we can be influenced by our social reality.8 9 Our brains are designed for the very specific purpose of helping us survive, it is entirely uninterested in making us see reality objectively.3 For example, if we sense a threat, we are flooded with emotions to persuade us take action to respond to the threat rather than objectively evaluate the situation. Our brain doesn’t rationally look through the evidence to determine if the threat is real or not, or what the best course of action would be to respond to it. Our emotions are imprecise signals that function whether or not they are warranted. Ultimately, our emotions and biases influence our perception of reality much more than we would like to think.10 When we realize this, the only sane option is to give our beliefs less weight.

One might argue that a single human mind is fallible, but humanity as a whole makes up for the errors of a single human mind. However, even humanity’s most rigorous system of knowledge, science, is subject to error and revision. There are many examples throughout history where a new theory comes along and corrects errors in a previous theory we thought was certain. For example, general relativity corrected gaps in Newtonian mechanics and has proven to be a more accurate model.11 Even something as fundamental and unchanging as the physical laws of the universe are constantly subject to discovery and revision. It is also important to note that Newtonian mechanics, although inadequate, is still useful for some contexts. This example shows that a theory’s truth is on a spectrum and its accuracy is subject to change. Newtonian mechanics is not true and general relativity is not true, they are just useful approximations that stand to be corrected. Likewise, It is impossible to predict what we might discover in the next hundred years that might make some of our current knowledge obsolete. How foolish would it be to claim that humanity is done learning just as we claimed in the Middle Ages. Uncertainty is not just where we start when we don’t know something, it’s a state that we will always be in when we acknowledge that there is always more to know.

A common rebuttal is from the vantage point of “common sense.” This is the most frustrating argument to me about uncertainty and skepticism because it comes off as a thought terminating cliche.12 Yes, there are certain facts about the world that we claim to know and they are relatively uncontroversial due to our common sense. These facts are rarely questioned, that’s why we typically don’t see much scientific literature being produced about whether or not jumping off of a 300 foot cliff will lead to death. However, humans have a tendency to overestimate their “common sense” and apply it to situations where more careful analysis is required. Often times, the truth is unintuitive. To continue the physics example, general relativity is much less intuitive than Newtonian mechanics because we have more everyday experience with it.11 If we can only rely on our beliefs being aligned with “common sense” then we will miss out on a breadth of knowledge. Furthermore, the fallibility of the mind means that our common sense is not as accurate as we might think.

Like all tools, uncertainty has the potential to be abused. It can also be a mechanism for dismissing evidence contrary to our beliefs, or in other words, confirmation bias. For example, one type of argument vaccine skeptics employ is some form of epistemic relativism.13 So, when shown evidence that supports the consensus that vaccines are effective, they will make a claim that obfuscates the weight of the evidence. They may say something along the lines of, “How do we know they are telling the truth” or, “There isn’t really a consensus in the scientific community” or, “Vaccines aren’t 100% effective.” They only bring this uncertainty up when it comes to information they do not want to hear. But, when the same skeptic listens to some alternative medicine guru or crackpot scientist, suddenly the epistemic relativism vanishes. Suddenly the charlatan they follow has all the answers. This reveals that the intention all along was not to be skeptical or rigorous, it was to only be skeptical of one type of evidence, evidence that they do not want to believe. It’s always good to be skeptical of information and evidence, but we can’t have our cake and eat it too. We cannot be skeptical or uncertain when it comes to evidence that does not support our belief and be certain and unquestioning when it comes to evidence that does support our belief. We should apply the same level of skepticism across the board otherwise we are just falling into the confirmation bias trap. We must ask ourselves if we would be as skeptical of new evidence that supports our belief as we would be of evidence that contradicts it.

Similarly, spreaders of disinformation and propaganda will try to evoke feelings of uncertainty in order to get people to fall into the trap of epistemic relativism. The goal of disinformation is not always to get people to believe a lie, it is to make them believe nothing so they don’t believe the truth.14 One way this is accomplished is through the firehose of falsehood technique, where a large number of messages are broadcast without regard for consistency or accuracy. By flooding people with many competing pieces of false information it becomes impossible to properly sort through the information and find the truth.15 This can create a vicious cycle because predisposition to epistemic relativism can predict inaccurate discernment of fake news.16 While uncertainty can help prevent against dogmatic beliefs it can also lead to a form of post-truth nihilism if we let it. It’s important not to give up on looking for the best approximation of truth.

Being Uncertain Is a Virtue

I believe the general willingness to change our minds about any of our beliefs is a virtue. However, I know this is a more controversial point since the qualities people admire are largely subjective. My aim with this section is to challenge typical cultural beliefs about uncertainty and explain the admirable qualities and social benefits that come out of positioning ourselves this way. When we acknowledge that our minds are fallible, we must turn to humility.17

Despite the common belief that changing your mind is weak, in reality, it is a courageous act. It shows yourself and others that you are confident enough to be vulnerable. If one can be wrong and grow from the experience without changing their self-esteem, then they are more confident than those who never admit they are wrong. Often the loudest, most assertive, and most stubborn are the least secure. Paradoxically, this insecurity is seen as strength and trustworthiness in certain situations. People flock to leaders who are loud, combative, and never show vulnerability. A common place we see this dynamic is in politicians and media personalities.18 We interpret a politician switching opinions as evidence that they would go back on their principles just to grab power, or an overall lack of integrity.19 To some extent, this might be true, but politicians are not normal people. They are supposed to represent a static set of beliefs that will be propagated into the government when people vote for them. The good news is, the vast majority of us are not politicians and we do not have to (and probably should not) act like them. I only bring up this edge case to show how popular culture can make us believe that to be seen as strong and well-liked, we have to be rigid, consistent, and certain. Certainty is useful if one wants to be a politician or celebrity, but in everyday life, a commitment to truth and humility will enrich our minds and communicate authenticity.

Here is an example that will help drive this point home. Say you are in a disagreement with someone (it could be political, personal, scientific, etc.). Imagine how the conversation will go if you say something along the lines of “I’m right, you’re wrong,” no matter what the other person says. Now imagine the conversation if you honestly put forth your opinion and acknowledge when the other person makes a good point. This establishes good-faith. You show the other person that you aren’t trying to “win,” you are just having an open discussion with them. You could even concede a few points when appropriate, and the other person will be more likely to concede some points as well. The point here is not to always agree with someone to avoid conflict, it’s to show how certainty and stubbornness can close you off from the truth and valuable perspectives.

Being charitable, arguing in good-faith, admitting when we are wrong, and admitting when we don’t know is extremely difficult. It can be especially difficult when it feels like other people are not doing the same. However, like Bertrand Russell said, being virtuous is difficult, but I believe it is worth pursuing.

Obstacles and What to Do About It

At this point, I have finished arguing for the benefits of shifting towards uncertainty, but actually doing it is easier said than done. I debated writing this section because it seems to slap my argument in the face even if the conclusion is correct. Sure, being uncertain is great and all, but we have millions of years of evolution that have shaped our minds to be resistant to the very concept. This section dovetails with the wealth of research on cognitive biases and heuristics employed by the human mind. Sometimes, the more I read this area of psychology, the more I lose hope. It’s easy to read all of this evidence and think that humans are hopelessly irrational idiots. We would all love to become more rational and intelligent, but instead, we are human. Is it even possible to do any better? The short answer is I don’t know. However, it’s first important to realistically set our expectations. The goal is not to become superhuman or completely eliminate our biases, or be “perfect” in any way. In fact, shifting towards uncertainty is accepting that our minds are fallible. In my opinion, becoming aware of what causes us to hold onto beliefs with certainty is the first step to becoming more rational.

Let’s revisit the example where you are trying to build a fence but add another dimension to it. We have seen that when you don’t know how to build a fence you are faced with two options: admit that you don’t know and seek out new information or lie to yourself about your knowledge. What would cause someone to be more likely to lie to themselves in this situation? Maybe in this situation, you view yourself as a “handyman.” This other piece of information in your mind creates internal conflict. A “handyman” would probably know how to fix a fence, but you don’t. This internal conflict is known as cognitive dissonance.20 To remediate cognitive dissonance, you can either alter your behavior (seek out new information), alter your beliefs (maybe you are not as handy as you think they are right now), or do neither.

Doing neither typically leads to confirmation bias or motivated reasoning - tools people use to protect their beliefs at all costs.21 The consequence is creating unreasonably certain beliefs that are disconnected from reality. When we fall into this trap, it becomes much more difficult to add any degree of uncertainty to our beliefs. Uncertainty is a threat to our deeply held beliefs, a threat that will ultimately lead back to the discomfort of facing our cognitive dissonance. This is why it can be so difficult to change others’ or our own minds. If our mind could not be changed under any circumstance, no matter the evidence we are presented, then that’s probably a sign we are engaged in motivated reasoning. As I mentioned earlier, all beliefs are provisional due to our fallibility, and if we think our belief is an exception, we are probably biased. When we have a vested interest in supporting a particular conclusion, we will be blind to alternative evidence, and ultimately, the truth.

Motivated reasoning is hardwired into our psychology, but the specific reason for a particular motivation can be varied. It could be due to how we were raised, childhood trauma, or who we surround ourselves with. I hypothesize that a very common reason is to protect ourselves from feeling inadequate. Coming to terms with the fallibility of our minds and the complexity of the universe can be incredibly daunting. Turning towards certain answers can be a way to escape this discomfort. It can often be much more comfortable to believe a lie than sit in uncertainty. I think part of the story is that people are not taught to deal with feelings of discomfort. People believe that discomfort is something that needs quick fixes even if the fix is not good for us. However, I don’t think that feeling inadequate is a warranted response to complexity. Nobody is perfect, making mistakes is a common human experience. All that matters is how we deal with our fallibility. Do we pretend that it doesn’t exist, or do we take action to improve?

Aversion to uncertainty doesn’t just come from internal conflict, external pressures might force us into haphazard beliefs and assumptions. The need for cognitive closure is a principle that underlies this process.22 Time pressure may force us to reach a conclusion, in which case, uncertainty might not be realistic. The key is what we do after the time pressure goes away. That belief might have served us well for a period of time, but that doesn’t necessarily mean that it is accurate. Acknowledge that it was the best we could have done given the resources and information we had at the time, but it still could be wrong. The need for cognitive closure can also kill our creativity because it shuts down the exploration of alternative ideas.23 After the pressure is gone, we must combat our cognitive closure with curiosity for new information and ideas.

Another source of external pressure for inertia can be professional. Similar to the discussion above about politicians, there may be particular incentives in place that would make it too costly to change our mind. If we have made a career espousing a particular set of beliefs, changing our mind could put our career at risk. A political commentator might lose followers if they switch sides, or a scientist might lose their reputation if they go back on their theory. Furthermore, our success might give us reason to become infatuated with our own mind, falsely assuming that our mind in particular is not fallible. There is a particular phenomenon called “Nobel disease” where Nobel Prize winners become emboldened by their award to make outlandish and pseudoscientific claims outside of their field of expertise.24 The lesson we can take from all of these examples is that nobody is immune from bias and irrationality, and we should always doubt our beliefs regardless of our success.

Lastly, uncertainty inherently requires that we assign some weight or probability to our beliefs, and people are notoriously bad at intuitive statistical thinking.25 It is much more difficult to think in probabilities than in black and white. In Maria Konnikova’s book The Biggest Bluff, she explains how the game of poker is all about “betting on uncertainty.”26 In poker, you have to confront the confidence of your beliefs because you have to place bets on those beliefs. According to Konnikova, this feature of poker makes it useful for training our probabilistic thinking because the consequence of mistaking your belief as 100% certain instead of 60% certain will lose you money. When we have something at stake, we become much more aware of the possibility of being wrong and are incentivized to think critically about what we know and don’t know. This could be one of the reasons that prediction markets are so accurate.27 It could also be because prediction markets ask people to give their beliefs in probabilities instead of absolutes.28 Therefore, we don’t literally have to put our money where our mouth is. It’s simply about prompting ourselves in a way that promotes information seeking and critical thinking. Next time we catch ourselves with an overconfident belief, we can ask, “What’s the probability that I’m right if I had to bet my money on it?” Of course, this isn’t foolproof as evidenced by gambling addictions.

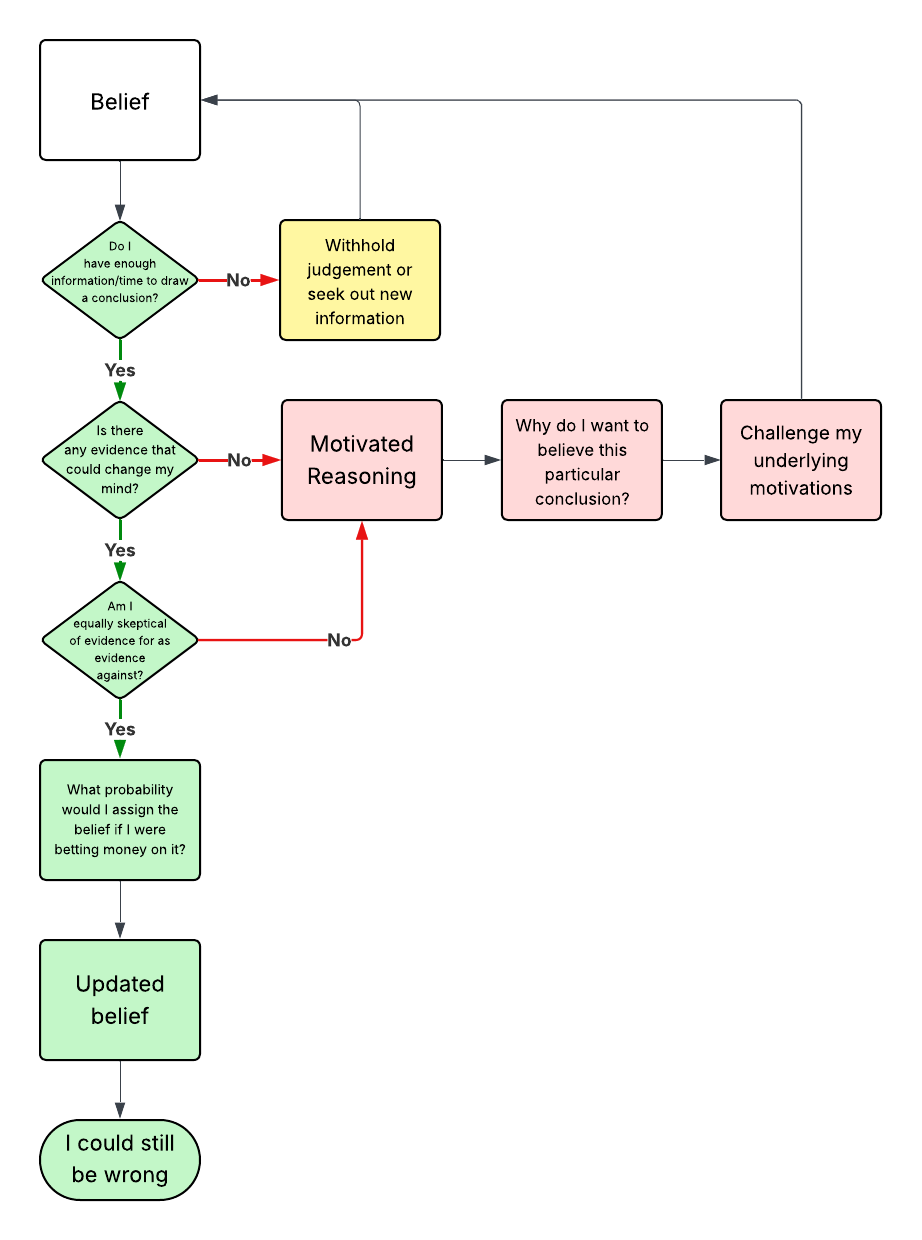

There is no surefire way to combat false certainty and to deal with the discomfort of uncertainty. However, maybe the best path forward is to foster self-awareness through Socratic questioning.29 When we ask ourselves questions to stimulate critical thinking, we can become more aware of what causes us to think the way we do. This is similar to Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, a common form of treatment for mental health conditions. In fact, according to this paradigm, one source of peoples’ distress comes from their faulty, often rigid beliefs about themselves and the world.30 Who do you think will be happier, the person that says things like, “I never do anything right, everyone is evil and out to get me,” or the person that says, “I sometimes make mistakes, there are some good people and some bad people in the world.” An aspect of the treatment is helping people challenge their absolute beliefs and replace them with more adaptive ones.31 These more adaptive beliefs are often more nuanced and gray, similar to the previous discussion about thinking in probabilities. While it may seem a bit contrived, I created a flowchart to make the process clear in my mind.

Just so it’s not too abstract, here’s a hypothetical example going through the flowchart. Say you are deciding whether or not a new medical procedure is helpful. Suppose you start out with the belief that this procedure is extremely deadly and harmful. Then you ask yourself, “Do I have enough information and time to draw a conclusion?” Your response could be “no,” in which case you can either withhold judgment until you have more time to research the medical procedure or start the process of seeking out more information until you think you have enough evidence. So you start looking up articles and testimonials about the medical procedure. Now that you have enough information, you ask yourself, “Is there any alternative evidence that could change my mind?” If the answer is “No, there is nothing good I could be shown about this medical procedure to change my mind; it is definitely harmful,” then you are engaged in motivated reasoning. Next, you ask yourself, “Why do I want to believe this particular conclusion that this medical procedure is harmful?” After some reflection, maybe you realize that you have had bad experiences with doctors in the past and you have a deep distrust of the medical establishment. You can now challenge this deep distrust by questioning if it is rational. You might tell yourself, “Just because I’ve had a bad experience in the past doesn’t mean all doctors and medical procedures are bad.” Then you ask yourself, “Am I equally skeptical of evidence for the medical procedure and evidence against it?” If the answer is “No, I’m much more likely to believe people’s testimonies that claim the medical procedure harmed them than those that say it helped them,” you then realize that the reason you have this approach is because you think the positive testimonies are people secretly working for the company that does the medical procedure. Then you tell yourself, “Sure, there may be some shills, but surely there are independent testimonies and data that support the procedure.” Now you are able to look at evidence from both sides with a more unbiased approach. Based on the available data and expert opinions, you assign a 70% probability that this medical procedure is helpful if you were betting money on it. This is your new updated belief, going from 100% harmful to 70% helpful. Then you tell yourself, “I could still be wrong; new information will require me to update my belief.”

This example is obviously really simplified, and it may take a lot of time and iterations to get through the entire process. However, I believe it could be a good starting point to help guide us to more accurate conclusions.

Conclusion

Our fallibility is terrifying. Uncertainty is terrifying. However, to me, being utterly convinced of something false is even worse. To care about what is true, free from dogma, is to be in a constant state of uncertainty. It allows us to let go of our desired conclusions and opens us up to the complexity of reality. While it may be comfortable, protecting ourselves from the truth will only cause us more pain in the long run because it always catches up with us. If humanity’s willingness to admit ignorance propelled us out of the Dark Ages and into an era of extraordinary discovery, what could it do for our individual lives? In my opinion, embracing uncertainty will make us better thinkers, scientists, philosophers, and citizens. Though, in the spirit of this essay, I could be wrong.

Updates

08/16/2025

After some time reflecting on this writing, I realized I had failed to elaborate why any of this actually matters. I made my argument for how uncertainty helps us get closer to the truth, but I did not clearly explain why the truth matters. I glossed over this because I assumed that people want to have true beliefs. However, a rebuttal to this is that perhaps psychological comfort is more important than the truth. Perhaps some people need to create structures in their mind to make reality more palatable. Perhaps the benefit of comfort outweighs the cost of believing falsehoods. Sure, that can be a fine way to live life. I cannot get everyone to value what I value. This article came from my perspective, as someone who thinks the truth is important. All I can do is offer one last fleeting argument for why it may matter.

False beliefs can go one of two ways: they cause us direct harm or subtle harm. For example, say I have a belief, “I can fly,” and jump off a building and break my leg. Afterward, I will probably update my belief to, “I cannot fly.” My belief caused me direct harm, so I changed it. If I kept believing that I can fly after that, I would foolishly continue to cause myself direct harm. Now, say that I believe smoking is good for me. I spent my entire life believing that, smoked all my life, lived happily, and died at 67 years old. Some people throughout my life told me to stop because it was bad for me, but I didn’t think much of it since I felt fine. In this scenario, I lived my entire life without uncertainty about smoking but, the entire time, it was subtly harming me. However, if I hadn’t smoked, perhaps I could have lived to 77 years old. There was never any direct wake-up call that I needed to change my belief, but it was still consequential. Sure, there are probably plenty of things that are causing us to die more quickly. But the key distinction in this story is that I was made aware of it. Instead of updating my beliefs, I decided not to do anything about it because I wasn’t experiencing direct harm. In both cases, it seems to me that updating our beliefs to be truer is much better than living in a psychological bubble, but I will leave that up to the reader to decide for themselves.

Within this view, I’m assuming that beliefs have some form of consequence, but some beliefs are more subjective. In that case, it can be hard to give oneself any good reason to change one’s mind. At this point, can’t everyone just believe whatever they want? If that’s the case, then it’s even more important to give their beliefs less weight. For example, say I think carrot cake is the best cake. It would be absurd for me to give any weight to this as an objectively true belief. In this case, the default state for most people is uncertainty about the objective truth of the claim (this is not objectively the best cake for everyone) but certainty about the subjective truth of the claim (this is the best cake for me). However, if I were to believe that carrot cake is the best cake for everyone across time, then this would be within the category of belief I described throughout this article because it is subject to truth and consequences. Therefore, it would still be worth being uncertain about it, so I could debate what the best cake is with others and possibly change my mind to say chocolate cake is objectively the best cake.

Footnotes

-

Russell, Bertrand. Unpopular Essays. London: Routledge, 1995. ↩

-

Bang, Yvonne. “David Deutsch Explains Why It’s Good To Be Wrong.” Nautilus (blog), May 8, 2015. https://nautil.us/david-deutsch-explains-why-its-good-to-be-wrong-235417/. ↩

-

Hoffman, Donald D., Manish Singh, and Chetan Prakash. “The Interface Theory of Perception.” Psychonomic Bulletin & Review 22, no. 6 (December 1, 2015): 1480–1506. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-015-0890-8. ↩ ↩2

-

Steele, Katie, and H. Orri Stefánsson. “Decision Theory.” In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, edited by Edward N. Zalta, Winter 2020. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University, 2020. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2020/entries/decision-theory/. ↩

-

Harari, Yuval Noaḥ. Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind. Translated by Haim Watzman and John Purcell. New York, NY: HarperCollins Publishers, 2015. ↩

-

“Fallibilism | Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.” Accessed May 24, 2025. https://iep.utm.edu/fallibil/. ↩

-

Thornton, Stephen. “Karl Popper.” In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, edited by Edward N. Zalta and Uri Nodelman, Winter 2023. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University, 2023. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2023/entries/popper/. ↩

-

Gregory, Richard L. “Visual Illusions.” Scientific American 219, no. 5 (1968): 66–79. ↩

-

Kuran, Timur, and Cass R. Sunstein. “Availability Cascades and Risk Regulation.” Stanford Law Review 51 (1999 1998): 683. ↩

-

De Martino, Benedetto, Dharshan Kumaran, Ben Seymour, and Raymond J. Dolan. “Frames, Biases, and Rational Decision-Making in the Human Brain.” Science (New York, N.Y.) 313, no. 5787 (August 4, 2006): 684–87. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1128356. ↩

-

Horizon, Beyond the. “The Fallibility of Knowledge, Newtonian Mechanics, and General Relativity.” Medium (blog), April 17, 2024. https://medium.com/@prmj2187/the-fallibility-of-knowledge-newtonian-mechanics-and-general-relativity-91cdccb19bd3. ↩ ↩2

-

Lifton, Robert Jay. Thought Reform and the Psychology of Totalism: A Study of “Brainwashing” in China. The Norton Library 221. New York, NY: Norton, 1963. ↩

-

Fasce, Angelo, Philipp Schmid, Dawn L. Holford, Luke Bates, Iryna Gurevych, and Stephan Lewandowsky. “A Taxonomy of Anti-Vaccination Arguments from a Systematic Literature Review and Text Modelling.” Nature Human Behaviour 7, no. 9 (September 2023): 1462–80. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-023-01644-3. ↩

-

Dunwoody, Philip T., Joseph Gershtenson, Dennis L. Plane, and Territa Upchurch-Poole. “The Fascist Authoritarian Model of Illiberal Democracy.” Frontiers in Political Science 4 (August 10, 2022). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2022.907681. ↩

-

Anderau, Glenn. “Fake News and Epistemic Flooding.” Synthese 202, no. 4 (September 24, 2023): 106. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-023-04336-7. ↩

-

Rudloff, Jan Philipp, and Markus Appel. “When Truthiness Trumps Truth: Epistemic Beliefs Predict the Accurate Discernment of Fake News.” Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition 12, no. 3 (2023): 344–51. https://doi.org/10.1037/mac0000070. ↩

-

Leary, Mark R. “The Psychology of Intellectual Humility,” n.d. https://www.templeton.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/JTF_Intellectual_Humility_final.pdf. ↩

-

Crowe, Jonathan. “Human, All Too Human: Human Fallibility and the Separation of Powers.” Australian Public Law. Accessed May 24, 2025. https://www.auspublaw.org/blog/2015/07/human-all-too-human. ↩

-

Slattery, Gram, Helen Coster, Gram Slattery, and Helen Coster. “JD Vance Once Compared Trump to Hitler. Now, He Is Trump’s Vice President-Elect.” Reuters, November 6, 2024, sec. United States. https://www.reuters.com/world/us/jd-vance-once-compared-trump-hitler-now-they-are-running-mates-2024-07-15/. ↩

-

Harmon-Jones, Eddie, and Judson Mills. “An Introduction to Cognitive Dissonance Theory and an Overview of Current Perspectives on the Theory.” In Cognitive Dissonance: Reexamining a Pivotal Theory in Psychology (2nd Ed.)., edited by Eddie Harmon-Jones, 3–24. Washington: American Psychological Association, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1037/0000135-001. ↩

-

Su, Siyan. “Updating Politicized Beliefs: How Motivated Reasoning Contributes to Polarization.” Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics 96 (February 1, 2022): 101799. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socec.2021.101799. ↩

-

Kruglanski, Arie W., and Shira Fishman. “The Need for Cognitive Closure.” In Handbook of Individual Differences in Social Behavior, 343–53. New York, NY, US: The Guilford Press, 2009. ↩

-

Cunff, Anne-Laure Le. “Reopening the Mind: How Cognitive Closure Kills Creative Thinking.” Ness Labs (blog), November 24, 2022. https://nesslabs.com/cognitive-closure. ↩

-

“Nobel Disease.” In Wikipedia, May 5, 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nobel_disease. ↩

-

Kahneman, Daniel. Thinking, Fast and Slow. 1st pbk. ed. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2013. ↩

-

Konnikova, Maria. The Biggest Bluff: How I Learned to Pay Attention, Master Myself, and Win. New York: Penguin Press, 2020. ↩

-

Berg, Joyce E., Forrest D. Nelson, and Thomas A. Rietz. “Prediction Market Accuracy in the Long Run.” International Journal of Forecasting, US Presidential Election Forecasting, 24, no. 2 (April 1, 2008): 285–300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijforecast.2008.03.007. ↩

-

Dana, Jason, Pavel Atanasov, Philip Tetlock, and Barbara Mellers. “Are Markets More Accurate than Polls? The Surprising Informational Value of ‘Just Asking.’” Judgment and Decision Making 14, no. 2 (March 2019): 135–47. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1930297500003375. ↩

-

Carona, Carlos, Charlotte Handford, and Ana Fonseca. “Socratic Questioning Put into Clinical Practice.” BJPsych Advances 27, no. 6 (November 2021): 424–26. https://doi.org/10.1192/bja.2020.77. ↩

-

Aeon. “The Danger of Absolute Thinking Is Absolutely Clear | Aeon Ideas.” Accessed May 24, 2025. https://aeon.co/ideas/the-danger-of-absolute-thinking-is-absolutely-clear. ↩

-

Chand, Suma P., Daniel P. Kuckel, and Martin R. Huecker. “Cognitive Behavior Therapy.” In StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, 2025. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470241/. ↩